Pinnacle at Symphony Place Green Roof , Nashville, TN

Pinnacle at Symphony Place Green Roof , Nashville, TN

The following is a brief email interview we conducted with Steven Peck, founder and president of Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, a non-profit industry association promoting the planning, designing and building of green roof, and green walls.

GrID: It was good news to hear the green roof market continued to expand in 2010. We hope the trend continues. You were recently quoted in The Dirt, stating this expansion constituted an addition of 8-9 million square feet of green roofs. Can you provide more detail into what characterized this expansion (i.e. type of green roofs, clients, project types, etc)?

Steven Peck: We just posted a report on the industry survey at www.greenroofs.org that contains more detailed information about what types of buildings are green roofs being implemented on, the types of green roofs being installed, locations etc. It is a free, downloadable report that contains all of this information.

GrID: You acknowledge a lot of this growth is taking place in cities that are encouraging the development of green roofs through “significant public policy support”. What best policy or program practices are you seeing used most effectively in the United States? Any others you would like to see instituted?

Steven Peck: Most of the policy tools being used in the United States are economic in nature, in the form of tax incentives, increases in floor area for new developments, and grants averaging $5 per square foot. There are also procurement requirements for government buildings – a good place to start – as well as for any building that is receiving some for of government financial assistance. For publicly owned buildings, the fact that green roofs, if properly design, installed and maintained by a Green Roof Professional (GRP) extend the life expectancy of the waterproofing by two times or more, is a significant economic benefit for tax payers. Billions of square feet of flat roofs are torn off and replaced each year at enormous public and private cost.

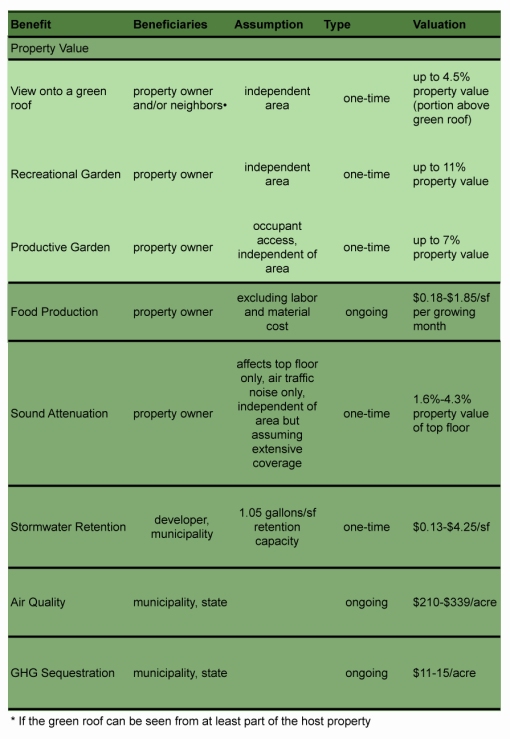

The new versus retrofit markets are different, and the nature of the incentives to encourage green roofs varies from building type to building type, because the economics are very different. This makes it difficult to generalize about effectiveness. In buildings where green roofs can provide more direct benefits to the building owner – like condomiums, buildings that are air conditioned, schools and hospitals, the economic case is stronger. In buildings that are very cheaply constructed, not air conditioned, and the roofs are innaccessable to the occupants or public, greater government incentives are likely to be required owing to the fact that the benefits are more in the public realm. For example, green roofs are widely regarded as a best management practice by governments in dealing with the need to reduce and slow down stormwater, which in many cities results in significant water quality problems. So building owners can meet regulatory requirements by installing green roof systems.

In Canada, two jurisdictions, the City of Toronto and the City of Coquitlam have made green roofs a requirement in various classes of new development. The Green Roof By-Law in Toronto requires that all buildings over 2,000 square meters of floor area (with the exception of new industrial buildings) must install a green roof. This policy has already resulted in an estimated 1 million square feet of new green roofing that is now in the planning phase. It also levels the playing field and provides the design community with the opportunity to skip the ‘justification’ of the green roof and move right to ‘how do we get the most benefit’ from the green roof stage.

GrID: The new ANSI Fire and Wind standards seem to potentially have a big impact on the aesthetics of green roof design. Can you give us some insight into why and how they were developed? What has been the reaction to the new standards from the design side of the industry? Are they being widely used?

Steven Peck: The standards were developed because of largely unfounded concerns about these issues, but we need to address them in order to remove a potential regulatory barrier. During the development of the standards, we tried to maintain as much flexibility as possible in terms of design. It remains to be seen how widely these standards will be adopted, and ultimately what effect they will have on the aesthetics.

GrID: Green roofs can be initially significantly more expensive than traditional commercial roofing. As the green roof market has matured, are you seeing pricing coming down and/or seeing creative financing mechanisms that make it easier for property owners to choose to build a green roof on a new or existing building?

Steven Peck: Generally speaking, as a market begins to mature prices drop as a result of competitive pressures, more efficient implementation, and innovation in product and service delivery. This has happened in mature markets like Germany, and it is happening in more mature markets in North America. There is a danger however – buyer beware – that in just using price as a determinant, you may end up with a green roof system that fails to work effectively. These are engineered systems and all of the parts have to work together to achieve water tightness, structural integrity and the long term health of the plants. We’ve spent 10 years developing professional training programs in order to establish and promote best practices in the industry. This has culminated in the development of an occupational standard for a Green Roof Professional. There are more than 450 GRPs in the marketplace, so make sure that you are working with a GRP to help to ensure that your green roof doesn’t disappoint you.

GrID: What trends are you seeing in the green roof industry? What will the future of green roofs look like?

Steven Peck: We have recently developed three new courses that reflect some of the trends in the industry. Advanced Maintenance we launched in April in Washington to provide more detailed information on how to design, budge and implement effective maintenance practices. Maintenance neglect is one of the main causes of problems on a green roof. In November of last year, we launched a half day course on Urban Rooftop Food Production, a hot topic these days. We’ll be providing training in Toronto and New York this summer, two jurisdictions where there is a strong urban food movement. Water. In many regions, water shortage is already a problem, and only likely to get worse. Last year we developed an introductory course on Integrated Building and Site Water Management, in partnership with the American Society of Irrigation Consultants. This half day course will be available online, in our Living Architecture Academy, in June. Increasingly, green roofs will be integrated with other forms of green infrastructure, like green walls, and be designed to perform multiple functions – cool cities, biodiversity, food, improve photo-voltaic efficiency. We’ve still only scratch the surface of the full potential of these technologies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.